Are autonomous cars safe to drive?

Data shows that human error is responsible for 95 percent of all car accidents. According to the National Highway Safety Transportation Administration (NHTSA) roughly 32,300 people were killed in car accidents in 2011.

Drunken and distracted driving – two things an autonomous car can never do – were responsible for 13,209 of those deaths.

A study by nonprofit Eno Center for Transportation predicts that if only 10 percent of the cars on the road were self-driving, accidents would be cut by 211,000 a year, deaths would drop by 1,100 and the economic savings would hit $22.7 billion.

When 90 percent of the cars are autonomous, 4.2 million accidents would be avoided, a whopping 21,700 lives would be spared and the monetary savings would be an astronomical $450 billion.

“A world full of self-driving vehicles would radically change the insurance industry by eliminating the human error that accounts for the majority of vehicle crashes,” says Bill Hampton of Autobeat Group, which publishes industry data and analysis. “Look at it this way: What is the cost of insuring a person to be vehicle driver vs. insuring the same person to be a passenger on a bus, train or plane?”

A drop-by-drop rollout that leaves car owners in control means savings may not be as substantial, or as obvious. Incremental advances such as collision-avoidance systems usually aren’t accompanied by a specific insurance discount. While the vast majority of survey respondents reported they had at least one of the following computer-controlled safety features on their cars, only the first, anti-lock brakes, routinely nets a discount:

- Anti-lock brakes: 82.2%

- Electronic stability control: 28.2%

- Lane-departure warnings: 11.5%

- Backup camera: 18.6%

- Automated parking system: 5.3%

- Collision warning or collision avoidance system: 7.3%

“We do not currently provide discounts based on specific safety features,” says Jeff Sibel, spokesperson for Progressive Insurance. “However, if a particular vehicle is safer and has lower claims costs, those lower loss costs will be reflected in the premiumThe payment required for an insurance policy to remain in force. Auto insurance premiums are quoted for either 6-month or annual policy periods..”

Who trusts autonomous driving vehicles?

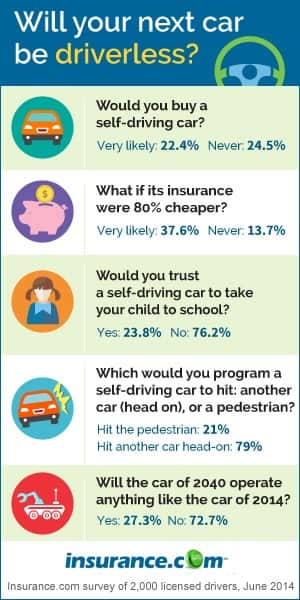

In spite of dramatic evidence to the contrary, 61 percent of the survey respondents said they would make better decisions behind the wheel than a computer could.

Only 31 percent would let the computer drive the vehicle whenever possible.

Over 75 percent would not trust a fully autonomous vehicle to drive their child to school.

All of this bodes well for traditional automakers that are rolling out individual autonomous features in their otherwise familiar-looking cars. Nissan, for example, is aiming for cars that can autonomously handle city traffic in 2016, lane-changing in 2018, and intersections in 2020.

But true self-driving cars, Nissan warns in its product roadmap released in mid-July, “remain a long way from commercial reality. They are suitable only for tightly-controlled road-environments, at slow speeds, and face a regulatory minefield.”

Yet Google says its research has shown that we quickly learn to trust AVs. While humans paid close attention to the vehicle and the road at first, passengers eventually become indifferent. “Humans are lazy,” said Nathaniel Fairfield, a technical lead with Google at the Embedded Vision Summit in May. “People go from plausible suspicion to way overconfidence.”

Who are driving autonomous vehicles?

Google’s latest prototype doesn’t seem very carlike. It is shaped like a pod and has a top speed of 25 mph. It lacks a steering wheel, gas pedal and brake pedal.

Google hopes to get at least 100 of them built and out on the road soon for testing, mainly around its Mountain View, California, campus. If the testing goes well, the top speed will go up, and new prototypes will hit public roads.

There is no consensus on when automakers will have a fully autonomous vehicle available. A number of carmakers have predicted self-driving cars will be on the road by 2020 – yet just four states -- Nevada, California, Florida and Michigan – and Washington, D.C. allow testing of autonomous vehicles out on the road, and all of them require a human being behind the wheel.

Doubters abound. IHS Automotive, an industry research firm, predicts it will be closer to 2035, and most experts believe it will be 2045 before a significant number of autonomous vehicles will be on the road.

Hampton agrees, “I suspect we'll first see self-driving cars on expressways only, cruising in their own specific lane. This could happen by 2020, but a world where self-driving cars can go everywhere and handle door-to-door trips is more like 20 years away.”

Are you ready for a car that drives itself?

Are you ready for a car that drives itself?